Hicks, J. R. The Theory of Wages

Regular price $3,500

London: Macmillan & Company, 1932. First edition of Hicks’ first book, an attempt at a careful and complete restatement of the marginal productivity theory. In the book, Hicks developed the microeconomics of wage determination in competitive and regulated labor markets. This work also introduced the famous concept of “elasticity of substitution” between capital and labor, which became his basis to dispute Karl Marx's theory by arguing that labor-saving technological progress does not necessarily reduce labor’s share of income. The book became a standard textbook on labor economics for decades.

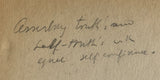

Pasted in to rear is an autograph letter signed by Hicks to fellow economist Jacob Marschak. Circa 250 words over two-pages.

Dear Marschak,

I am sorry to have been so long before answering your letters.

I certainly did not mean to imply that the elasticity of demand for labour being greater than one would be deemed a priori.

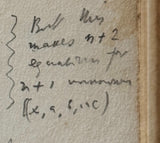

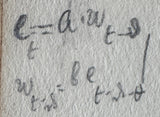

The note on p. 100 is certainly badly expressed, especially as I did not really need this condition for my argument! But I was led into certain expression because I did feel convinced that the long run elasticity must be in fact > 1; and this for the reasons you suspect. I could not believe that the elasticity of supply of the other factors (long-period elasticities gains) were likely to be very negative – I should on the whole expect that their curves won’t be far from zero; and if this is so, the <mathematical expression> formula gives what seems a quite impossibly low value for σ if λ < 1. (This with a view to the Bowley calculation.)

But I don’t nowadays put much confidence in all this. I think I should now approach the problem by regarding the <illegible> non-labour means of production as the “<illegible> factors whose elasticity of supply (ε), has to be considered.

And I should bring in most of the "capital" complications (discovery, etc.) on the demand side. But this would probably mean a reconsideration of the “relative share” statistics. Anyway it is all rather vague.

Yes, I agree that your diagram will <illegible> do. But I hope your research will throw more light on the question than (I am sure) mine has done.

Autographed material from John Hicks is quite rare, and none of his letters, and few signed books, appear in book auction records.

A very good copy lacking the scarce dust wrapper, spine tips rubbed, foxing to side of text block, weakness to the hinge between pages 96 & 97, and bookseller’s label from B. H. Blackwell of Oxford (Marschak, it should be noted, held positions at Oxford from 1930 – 1939).

John R. Hicks received the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (jointly with Kenneth J. Arrow) in 1972 for his pioneering contributions to general equilibrium theory and welfare theory.

One of the most important and influential economists of the twentieth century, the trail of the eternally eclectic John Richard Hicks is found all over economic theory. Hicks made major contributions to many areas of 20th-century economics; four, in particular, stand out. First, he showed that, contrary to what Karl Marx had believed, labor-saving technological progress does not necessarily reduce labor’s share of the income. Second, he devised a diagram—the IS-LM diagram—that graphically depicts John M. Keynes’s conclusion that an economy can be in equilibrium with less-than-full employment. Third, through his book Value and Capital (1939), Hicks showed that much of what economists believe about value theory (the theory about why goods have value) can be reached without the assumption that utility is measurable. Fourth, he came up with a way to judge the impact of changes in government policy. He proposed a compensation test that could compare the losses for the losers with the gains for the winners. If those who gain could, in principle, compensate those who lose—even if they do not actually and directly compensate them—then, claimed Hicks, the change in policy would be efficient.

“How is one to assess an economist whose legacy runs as wide and deep as that of John Hicks? The quintessential ‘economist's economist’, Hicks cannot be said to have founded a ‘school’ - unless one were to count the generation of eclectic and critical Neo-Walrasian theorists inspired by his visionary but careful work, such as Morishima, Hahn and Negishi. But Hicks was for the most part a lone thinker, part of every school and thus part of no school. If any, his school was ‘economics’.

Hicks himself claimed to have created no new economics but simply to have spent his life understanding, formulating and channeling the ideas of the Continental and Keynesian schools and his own historical, philosophical and practical reflections. In a sense, he may have been right - but he analyzed and extended them in a meaningful and challenging way and thus transformed economics in the process.

In many ways, Hicks's scholarly output is a perfect demonstration of how economics should be done: without partisanship for pet theories, without ideological quibbling, his own strictest critic, learning from all and everywhere, constantly searching for new ideas and staying glued to none. Hicks's approach to economics was informed by all the best qualities of the scientist, poet, philosopher and practical man, and he let none of these tendencies overreach themselves and overwhelm any other. In this sense, no economist before or since Hicks, has achieved such ‘Olympian’ scholarship.” (The History of Economic Thought)

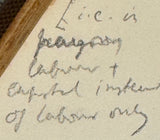

The book is annotated in pencil, presumably by Marschak, with the summary "Assuming truth's and half-truth's with equal self confidence" written to the front free end paper.

Jacob Marschak was an “important developer of economics information theory and a contributor to the early study of econometrics…Marschak’s major work was done in an obscure but important area of conceptual economic theory helping develop methodology for mathematical problem solving” (NY Times obituary). Not mentioned – because not known at the time – is that three of Marschak’s doctoral students went on to win the Nobel Prize for Economics: Leonid Hurwicz (2007), Harry Markowitz (1990) and Franco Modigliani (1985).

Marschak was impressed by the need for quantification of economics. His 1931 paper on the elasticity of demand was a landmark in econometric analysis, and as head of the Cowles Commission from 1943 – 1948, Marschak can be given credit for getting the ball rolling for the development of Neo-Walrasian economics and econometrics in the post-war era.

Marschak's contributions to economic theory in this phase were dominated by his interest in the concept of uncertainty. Already in his classic 1938 papers (one with Helen Makower) on monetary theory, Marschak set down the basic ideas for portfolio theory, in which risk was acknowledged to play a role. His encounter with the work of John von Nemann and Oskar Morgenstern (1944) led him to write his famous 1950 exposition of the axiomatization of choice under uncertainty, when he introduced the infamous "independence axiom".

It was specifically in the theory of information, the theory of "teams" and decentralized organizations where Marschak was to make his name (1954, 1968, 1971, 1972). He is renowned for having developed the theory of stochastic design as a way of statistically measuring demand. It was Marschak who helped introduce modern information theory into economics via Shannon's formalization of information via the mathematical theory of communication.

Kenneth J. Arrow, himself a Nobelist, wrote “Marschak became a leader of research organizations at a relatively young age in Germany, and later—with his increasing recognition—was director of the Oxford Institute of Statistics (1935-1939) and of the Cowles Commission for Research in Economics at The University of Chicago (1943-1948)—a fertile period that greatly influenced the course of economic analysis in several diverse fields. Only after 1948 did he begin to make the contributions to economic analysis that are most distinctively his own. Yet in curious ways, the subject matter of his later studies was consonant with his earlier career. An organizer of economic research, he became a theorist of organization. A student and critic of new developments in economic analysis, he developed the economics of information. A skeptic distrustful of received dogma, he studied the economics of uncertainty.

Another characteristic of Marschak's work was his consistently interdisciplinary approach. Some of his early papers dealt with class structure and the emerging phenomenon of Italian fascism. From 1928 to about 1953, though his titles stayed more narrowly within the field of economics as it was then understood, the papers themselves not infrequently contained broader notions derived from politics, sociology, and—later—individual psychology. His work on information and organization, for example, led to a series of experimental and theoretical studies on the psychology of decision making, while during his last fifteen years he organized an interdisciplinary behavioral sciences seminar that proved a main source of contact among mathematical modelers with widely divergent interests.”